The story of Mordecai Miller

Enclosed is the personal story of our father, Miller Mordecai, as he wrote on his 80th birthday.

Miller (or Muller) Mordecai was the son of Sonia (Sara) from the house of Bernstein, and Eliezer Miller.

Their address in Lodz was –28 Pułk Sterzelców Kaniowskich No.11

My father, Miller Mordecai, born in Lodz in 1924, was left alone in the world after the war, without knowledge of any relative, even distant.

His parents were called Sara and Eliezer Miller. He had a brother, Benyamin, and a sister, Esther, the eldest.

To the best of his knowledge, they all died. As a child, he heard about relatives who went to the United States, but he remembered no names.

Is there any way to search for relatives via the community of the survivors from Lodz?

Thanks,

Sara Helman-(Miller) 052-6320514 mrshellman@gmail.com

Amnon Miller 052-6200815 amnon.miller@gmail.com

Dad - life story – Miller Mordecai/Michael (Michal) ID 1091735

The odyssey began on September 1st 1939. The Nazis hadn't entered Lodz yet. After a week or so the soldiers entered, not the S.S. Everybody hoped we would survive that. Will they be able to kill 300,000 Jews? Anyway, everything was “all right”. After a week, the S.S and Gestapo entered. The first thing they did was to catch Jews for a “work”. Commands of the Nazi government were published. They first caught the bearded people. They didn't cut the beard, but just tore it off with its roots. Women were commanded to clean the streets – not with brooms, but with hair brushes and underwear.

Going up to Piotrkowska Street, which was formerly populated only by Jews and Germans, was forbidden for Jews.

I had some luck. The gymnasium of Itzhak Katzenelson was turned into headquarters of the Gestapo. We lived near the school and I was supposed to study there. For some reason, a young officer approached me and demanded I would clean for him. I cleaned for him and he asked me questions. First, he asked what my name was. When I said my name was Miller, he looked at me and said in German, “A Jew? with the name of Miller and blue eyes?” (I knew German since I had learned it in school). Anyway, the treatment of me was good.

While I was working there, I saw how lucky I was. I looked through the window and saw the abusing to the Jews. They turned the sports hall into a stable of horses, and the Jews had to clean with buckets and to water the horses. I saw the bumps they all got. I heard only in German – Los Verfluchten (get going, cursed). At 2 o’clock, he told me to go home.

I asked him to give me a letter so that I wouldn't be caught in the way home. He gave it to me so that I would be able to come to him tomorrow at 8 o'clock, and gave me a loaf of bread for the way. There was a problem with the bread. Esther couldn't go out, and Benyamin couldn't too, as he would be immediately arrested, since he was in the age of enlistment to military service.

There was a curfew in the city. Jews could only go out from 8 o'clock to 5 o'clock. I went out to stand in line for bread at 3:00 am. I hid in one of the gates of the bakery in which the distribution was taking place. When I was just close to get the bread, one Polish man told the supervisor (who was a Volksdeutsche – Polish German), “a Jew”, and pointed on me though I was wearing a yellow ribbon. I obviously got a kick and I was expelled from the queue. By the way, the Polish man was once a good friend of mine. We were together in the Scouts.

|

|

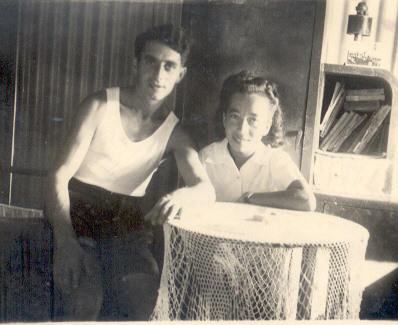

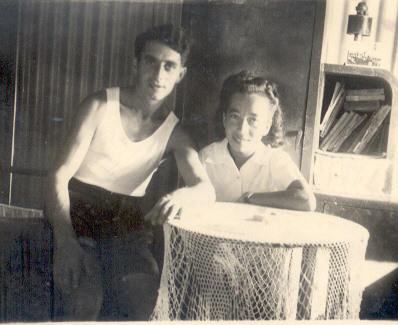

Mordecai Miller & wife Zipora in camp in Cyprus on 1948 |

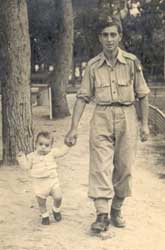

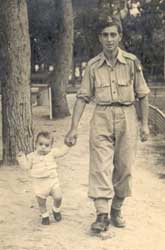

Mordecai Miller with daughter Sara as an Israeli "Givati" soldier upon immigration to Israel מרדכי

מילר עם

|

The life in Lodz was like that. We had a sewing workshop and many clients were Germans. Rodolph, one of the clients, once entered the sewing workshop, and didn't call “Mister Leon” to my father any longer. He came wearing the Hackenkreuz (Swastika) on the sleeve. He knew the Jews were going to go into the ghetto or to be killed, but immediately, in command – “I want this fur to be ready at 5 o'clock”. Dad said – “How is it possible?” “Shut up, Jude” he shouted. “I'm waiting at 5 o'clock.” Everyone worked to finish the fur. At 4 o’clock, I took the fur to give it to the German. I took a carriage (dorożka) and the coat and rode. I didn't remove the ribbon maybe they didn't know me, but the Polish people would inform the Germans. (A Polish person informed on a good friend of mine, and he was shot right there.) The carriage went up to Piotrkowska St. When we arrived, I saw from a distance a youth from Hitler Jugend directing the traffic. He called us to stop. We stopped. He looked inside, saw me and shouted: “Jude in Piotrkowska St.!”, and he didn't yet notice I wasn't wearing the yellow ribbon. First, I got a slap on the face. I was lucky. He stood in the side of the road, and I jumped to the pavement, straight to the gate.

In Lodz, the houses were built in a way that those in the corner were connected to the side street. I could get into Piotrkowska and exit to Poludniowa. I obviously did so. Incidentally, I knew Poludniowa well. There were meeting places of Hashomer and Agudath Israel there. I ran away but didn't throw away the fur (if I had known what would happen, I would obviously have thrown it away). I came to the German. He must have known it's our end, and therefore he hurried so much with his fur. I gave him the fur and he gave me 5 zloty “for a beer”. I went home on foot in another way and threw away the ribbon despite the danger (I have done it many times). I walked, and when I approached the street, a neighbor called Kowalski went outside toward me. He was a communist from the underground organization and he shouted “Don't dare going on. They are waiting for you at home.”

I burst into tears. What does it mean, not going? Dad and Mom, Beniek and Esther, are waiting for me. He gave me a note and told me to read and memorize it. In the note, there was an address of an estate, not far from Warsaw. The owner of the estate was Kowalski too, his uncle. I didn't go back home. After the war, the neighbors told me that the S.S had taken all the Jews to the ghetto, or to Chelmno, straight to extermination.

I came to the owner of the estate. The old man knew I was a Jew, but his children didn't. He told them he had hired me for work. I was there almost half of year. He was from the old generation. The Germans to him were as in Middle Ages “Prusaks” the Russians “Moskale”. I felt that his children suspected that I was a Jew. I have never gone to the village to wash myself. I have heard his children saying things like – we will have to build a monument for Hitler. He will finish off the Yids. I succeeded to get to Warsaw and from there I made efforts to pass and somehow get to the Russian side. However, this was when the Germans had already become established and it wasn't possible to move. In Warsaw, it was something like autonomy. I arrived somehow in Warsaw and from there I went on eastward. I jumped on a cattle train and arrived at a place that wasn't far from the new border between the occupied Poland and the part the Russians had occupied. I reached the border. I had some hundreds of zloty I had got from the old man, the owner of the estate. There was a rail station there, which led to Bialystok. I asked the owner of the place when does a train arrive to Bialystok. She told me that it could be soon, and it could be in a week. I was desperate. I paid her a little money and didn't tell her I was a Jew. I went up to the roof and waited. In the meanwhile, she entered holding a big rope on her arms and said in scorn, “One Jew has hung himself.” I was jealous of this Jew who had the courage to end up himself. I was then just something like 15 years old.

The train arrived and I succeeded to force my way inside. I went immediately to the top shelf. I looked outside. In the meantime, a “ticket seller” got into the train and called the people to get out and buy tickets. (This place was called the neutral part.) I don't know, but I called - “Don't go down, as anyone who goes down is lost!” I looked through the window and saw that everyone who went down was expelled back to the border, and was obviously taken by the Germans. I continued riding and somehow got to Bialystok. The refugees got there first aid from the Soviets. This all happened when the Germans had been in Poland almost for a year. I was in Lodz for half of year, and at Kowalski's almost for half of year. In Bialystok, the Soviets offered us to volunteer in coal mines. I was very afraid to be near the Germans, and immediately volunteered. The woman who wrote in Polish wanted to dissuade me from the intent to work. She told me that life here would be good.

We rode in the train for a whole month until we arrived. Interestingly, when we arrived, I was the only one from a hundred guys who agreed to work below. The rest worked above. It was worse there. It was cold and the portions of food were tiny.

After a month of ride and shaking, the train reached the city of Molotov. It was once called Perm, and is called so today, too, after the revolution in Russia.

The manager of the mine, a Jew, accepted us. I remember my talks to him, in which we told him about the cruelty of Nazis. He told me it was forbidden to talk like that because they were our friends. There were normal relations with the Germans then after Molotov pact. Interestingly, from all the guys who came, I was the only one who wanted to work below. For the matter of fact, above was worse. I worked pushing carts, stones and coal. The portions of food were larger below. Above, the coldness reached -40 degrees. After several months, a war between Asia and its friends started.

I continued working in the mines though I volunteered to the army. I wasn't accepted then, because I was “Polish”.

After the battles of Stalingrad I was sent to a labor corps in Engels, not far from Stalingrad, and at the meantime, obviously, the battles calmed down.

Our work was to repair the bridges the Germans had bombed, but this ended quickly. They were before surrender. At the meantime, they asked who was interested of working in the Donves in the mines. I immediately agreed, as I thought the Red Army might reach Poland. The battles were already in Ukraine. I thought I might be able to reach Lodz, and I was. I continued.

I left the mines and started to wander westward – on the train roofs, under the wheels, and in any other way. I remember we arrived in Bialystok (in the first time) and the war hadn't finished yet, the army still fought in Berlin. In Bialystok, I entered a former synagogue that was burnt. I saw addresses written in blood. I could read one of them, in which a girl wrote, “You can't believe what's happening here now. There are thousands of people here, and more are brought anytime.” This synagogue was burnt with the people in it. I went on. On the way, I entered Majdanek and saw the casks of fat from which the Germans had made soap. In the meanwhile, the war had ended, and when I approached Lodz, I threw away the army clothes and wore civilian clothes. Refugees from the camps started arriving to Lodz. I obviously didn't find anyone of my family. I contacted the Red Cross, and tried to do other things. In our apartment lived Polish people. The Joint organization from America helped a bit to the ones who came back. I was one of the first to arrive to Poland, as I had been a soldier in a work regiment, but as a Polish. I could maneuver a little. It was very dangerous then, because the ones who cooperated with Hitler established an army which fought the the Polish, communist rule founded by the Soviets. (I will write more about it.)

In Narutowicza St., the refugee Jews used to congregate. I also got there, hoping I would meet someone. I couldn't find anyone.

I entered the ghetto and found only Gypsies with suitcases who were collecting things and searching for Jewish money. I collected ghetto coins, the newspaper “Ghetto Zeitung”, Jewish policeman hats (in Israel, years later, I gave everything to Yad Vashem). In Narotowicza St., I suddenly met one Jew – Aharon Issac – who owned a farm for growing roses and had connections with the Netherlands. While talking with him, after he said he was a farm owner from Kutno, I asked him if he hadn't known Benyamin Miller. He called there: “Beniek? He was the nicest man who was in my farm.” (People went to his farm for the preparation of immigration to Palestine.) He told me that the authorities had given him his farm back and 100 German women for the work. He wasn't growing flowers anymore, but just vegetables. He asked me if I would like to work on his farm and be responsible for the workers. I obviously agreed.

I started to work, and actually – to supervise. The place was a city of a fire peace, Chelmno in which the Nazis had murdered the Jews of Lodz and my family. It was also a passage from Germany to the east.

One day, when we sat with Issac, three people wearing the British army clothes entered, speaking Hebrew to each other. I started to talk to them and they were very happy. One asked me about my details and I told him. He told me – why are you here, you can go with us to Bialystok (which was returned to Poland). We work with the Jewish Agency and Joint and rescue children who are still at the gentiles.

I promised I would come to Bialystok. There, we opened a school with Dr. Slepak. We named it after Bialik. The children were ones who arrived from Russia and lived with the gentiles. A Jewish officer from the Red Army, Ilya Ilushkin, helped us. They found many children with the gentiles.

We gave 30 thousand zloty, food parcels and so on to the ones who had given the children.

A girl, Hava Rozenstein, was once brought. She herded cows. At first, she didn't want to stay with us, but because of the necessities and the help of the other children, she stayed at last. We hid all these children, and then sent them to Krakow, to the known Lena Kichler. Members were killed by the Polish Fascists in other occurrences. While we were there, we opened the graves of the Jews who were killed and burned in the synagogue, and buried them in a graveyard. We also built a monument and a gravestone. The gravestone was probably dismantled. I give a picture of it to my daughter, Sara.

After I was a year in Bialystok, it was my turn to immigrate (illegally) to Eretz Israel.

When we were in the train to Warsaw, our train was attacked. The Polish Fascists demanded the Jews to get off the train. Some (from other cars) did and I watched them being shot and killed. One of them was a good friend of mine – Sher David, who was incidentally an officer in the Polish Army. After the murderers murdered five people of us, they escaped fearing of the Russian army that was still in Poland. I collected the pictures and documents and handed everything to our people in Warsaw.

I kept the pictures and documents, and sent them from the camp in Cyprus to an uncle of David from Tel Aviv, whose address I had.

How did I get to Cyprus?

From Poland, via the mountains, we went (secretly, obviously) to Austria, and from there to Italy. I was in Italy for one year, and then it was my turn to immigrate to Palestine. We went up to the ship “Shear Yishoov” and sailed. We wandered for one month, and encountered the English people in the coast. While sailing, we got a telegram about another ship of illegal immigrants, which is in trouble near Rhodes. In the middle of the night, we put a plank on the coast and they went up to our ship. It was obviously uncomfortable, but we were young and we managed. When we got to Eretz Israel, far from the coast, we were caught by the English people and were moved to the camps in Cyprus.

In the ship, I met Zipora, my future wife. I taught her Hebrew in Italy, but we were separated. We got married in Cyprus, in a kibbutz of Hashomer Hatzair.

In 1949, after we had been in the camp exactly for two years, we got released. I got a deferral from the army for arrangements and Sara was about to be born. We obviously didn't have an apartment. We entered for a short period to one of the orchards, and then we moved to the village of Salama (one of the ruins).

In the meanwhile, I was drafted to the army and served in a recruits’ base as a teacher for immigrants. While in service, I got a telegram from the officer of the city to get home quickly. There were strong floods then and we moved to live at a shed. I got a hitchhike with a half-track from there to Rehovot, and from there I got home, in hitchhikes too. I remember that I met my wife in the house, sitting with the baby on an inverted bench that was put between the edges of bed. The water in the shed already reached the knees. In the meanwhile, I finished the army in the rank of sergeant.

I was accepted to a work in Tel Aviv municipality, with decorations from the newspaper of Yedioth Ahronoth. I obviously derive pleasure from the children and from the grandchildren. Sara will add everything that may be added.

It was hard for me to write. I want to forget but I can't. After the war, I searched for Kowalski and then I was told that the Polish people informed the Germans on him. He was murdered by the Germans in tortures. I went to the estate, and was told that the children of the owner of the estate enlisted to fight with the authorities and to continue killing as many Jews as possible.

Mordecai Miller passed away on 17 March 2015. |